The Second Bank of the United States

Nicholas Biddle's Central Bank and Its Role in the Nation's Economy (1816-1836)

Stephen Campbell

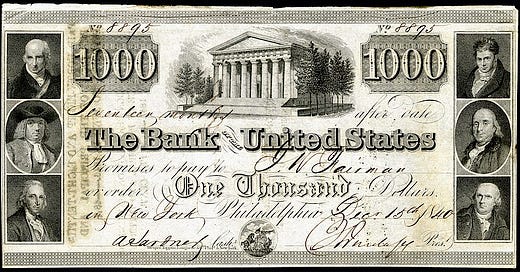

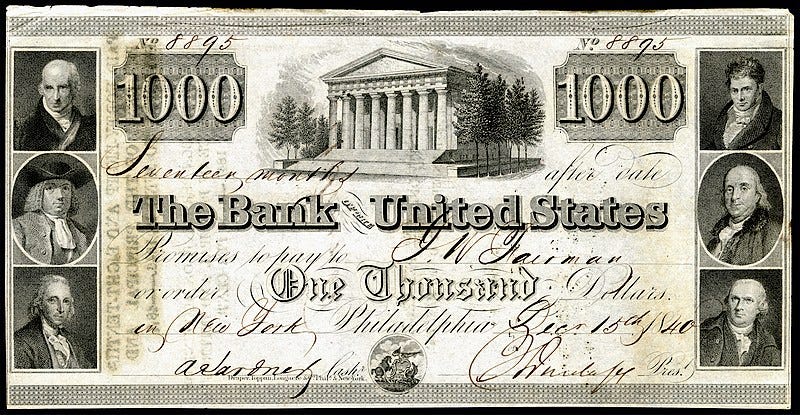

The Second Bank of the United States, also known as the United States Bank, National Bank, or BUS, was a central bank headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that existed from 1816 to 1836. Under the leadership of its president, Nicholas Biddle, the Bank became involved in a dramatic political showdown with President Andrew Jackson — a conflict known as the “Bank War” — that shaped many of the political, economic, and ideological contours of American life in the pre-Civil War era.

Origins of the Second Bank of the United States

In 1811, the Jeffersonian majority in Congress narrowly voted down an effort to renew the 20-year charter of the First Bank of the United States (1791—1811), the brainchild of the nation’s first treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton. The experience of financial instability and currency devaluation during the War of 1812 convinced many American politicians of the utility of a central bank. Therefore, Congress passed a bill creating a Second Bank of the United States in 1816, which President James Madison signed. Many of the merchants and financiers who had helped raise money for the war effort — among them, John Jacob Astor and Stephen Girard — lobbied successfully for a new bank.

Treasury Secretary Alexander Dallas and Representative John C. Calhoun from South Carolina helped craft the 1816 charter. The charter of the First Bank, itself influenced by the Bank of England, provided the model. The Second Bank of the United States would have a paid-in capital stock of $35 million. Private investors subscribed to 80 percent of these shares ($28 million) while the U.S. Treasury owned the remaining 20 percent ($7 million), making the BUS a hybrid public-private corporation.

At once a for-profit commercial bank, a repository for the nation’s public money, and the country’s main fiscal agent, the BUS helped to collect and distribute federal money and serviced the nation’s public debt. It accounted for about 20 percent of the nation’s banking capital, bank lending in the form of discounts, and bank notes in circulation. Of the nation’s entire stock of specie — gold and silver bars, ingots, and coins — the bank owned between 30 and 40 percent. There was no standardized national currency at the time like today’s Federal Reserve note, but BUS notes had some of the same characteristics. They circulated widely from hand to hand and were payable for all public debts, including customs duties and land sales. At a time when most businesses were small partnerships operating with only a local or regional presence at best, the BUS employed a nationwide army of over 500 agents and over 200 directors through its network of 25 branch offices and commercial agencies.

From its inception, the Second Bank of the United States was mired in controversy. Some of its directors violated expected norms and regulations by illegally issuing unsecured loans to themselves. The bank also contributed to a land bubble in the South and West that eventually burst, which played a role in creating the Panic of 1819. Its reputation among certain segments of the population also suffered as a result of several Supreme Court decisions that seemed to favor the interests of the wealthy over ordinary Americans. The unanimous decision in McColluch v. Maryland spearheaded by Chief Justice John Marshall upheld the National Bank’s constitutionality while putting forth a nationalistic view of the Constitution that minimized the role of federalism and states’ rights.

Central Banking Under Nicholas Biddle

Philadelphia patrician Nicholas Biddle became president of the Second Bank of the United States in 1823. Biddle brought to the Bank a number of innovative financial techniques and a more centralized management philosophy of regulation. The intent was to curb excessive lending among the country’s numerous state banks, propagate a stable and uniform currency, and stabilize variations in prices and trade. Because of the national bank’s large specie reserves (gold and silver), Biddle could relieve the inconveniences of temporary shortages of liquidity. As an economic and political nationalist, Biddle believed in keeping specie in the country whenever possible so that banks could continue to lend and avoid the possibility of deflation. On a handful of occasions he even rescued state banks from collapse.

All of these actions made Biddle a central banker and the Second Bank of the United States a central bank, though one should underscore that central banks today possess regulatory and monetary powers that are far more expansive and complicated. Many of the regulatory practices that Biddle implemented were not spelled out explicitly in the bank’s charter but evolved gradually as officers in the Second Bank of the United States realized the value of their large specie holdings. When the notes of state banks accumulated in the Bank's branches, Biddle instructed his cashiers to promptly redeem them in specie. Lower specie reserves would force state banks to contract their note circulation, thus minimizing the risk of inflation and excessive lending. Although Biddle did come to the aid of a handful of state banks, in general, the Second Bank of the United States prioritized its own safety, its profits, its political reputation, and its specie reserves above the concerns of the broader economy.

The Second Bank of the United States provided a means of national integration through its interregional network of branch offices, but it was not a public institution in the same way that the Post Office or Treasury Department were. It was, first and foremost, a private corporation that prioritized its private stockholders who were responsible for 80 percent of its capital. As such, the Bank’s stockholders elected 80 percent of the Bank’s directors while the presidential administration appointed the remaining 20%. The latter were the public directors who were supposed to provide a measure of public accountability since the Bank handled the public’s money. The private directors tended to be individuals with whom Biddle had a close working relationship, leading to agreement on key policy questions. In terms of its organizational structure, the Second Bank of the United States delegated a great deal of power to its president: Biddle served on all but one of the bank’s numerous committees, controlled over 30 percent of all of the votes allocated to the Bank’s stockholders for electing directors, and personally selected members of the all-important exchange committee that evaluated loan applications. In many ways, Biddle’s wishes became the Bank’s wishes.

In its capacity as the Treasury Department’s chief fiscal agent, the Second Bank of the United States provided convenient facilities for the collection and distribution of federal revenue. The bulk of the Treasury’s receipts came from customs duties and land sales and, secondarily, from dividends on subscribing to 20 percent of the bank’s stock. Added to this were small amounts of revenue accumulated from various taxes. In terms of government outlays (spending), the Second Bank of the United States helped to pay for veterans’ pensions, interest on the public debt, and the salaries of military officers and public officials, including judges, foreign diplomats, and members of Congress and the federal bureaucracy. Coordinating revenue and spending was a difficult process that required an interregional system of branch offices since most of the country’s revenue accumulated on the East Coast through tariffs while spending was required in every part of the union.

Managing the nation’s public debt was a major part of the Bank’s fiscal responsibilities. The public debt was comprised of various treasury bonds of differing maturities and yields. To promote foreign investment in the United States and gain access to British capital, the Second Bank of the United States established a formal partnership with Baring Brothers, a powerful merchant banking house in London. The Treasury Department issued bonds to the Bank, which sold them to exchange brokers like Prime Ward & King or Thomas Biddle & Company, who in turn would market them to Barings. From Barings, British investors could purchase U.S. Treasury bonds on London money markets. Because the BUS maintained so many different public and private responsibilities, it necessarily avoided risky loans for many years and kept large amounts of specie in its vaults. Its reserve ratio — the ratio of a bank’s monetary reserves in comparison to its liabilities — was about one-third whereas many state banks kept a riskier ratio of one-tenth or less.

How the Second Bank of the United States Worked

It can be difficult for modern-day readers to understand the mechanics of the antebellum era banking system, which was very different from today. There were hundreds of different financial institutions, each circulating their own localized currencies of various values, which were redeemable in gold and silver. Like most other commercial banks, the Second Bank of the United States loaned to borrowers and collected profits from interest. A merchant seeking a loan, for example, could come to a Bank branch office with some form of commercial paper such as a bill of exchange. The bank would take possession of the merchant’s bill, deduct interest up front, and offer Bank notes in return: a circulating medium that passed from hand to hand as cash.

In the strictest legal and constitutional sense, coins, including Spanish milled dollars, were the only currency with legal tender status in the antebellum era, which meant that individuals were obligated to accept them in payment for debts. But in day-to-day practice, notes issued by the Second Bank of the United States were the next closest thing. They were payable for all public duties, which is to say that Americans could use Bank notes to pay for customs duties, land sales, and local taxes. This helped give the Second Bank's notes legitimacy and a relatively uniform value in any part of the nation. Unlike notes from the Second Bank of the United States, most notes from state-chartered financial institutions were confined to a local or regional circulation.

The Bank started circulating millions of dollars of credit instruments known as bills exchange in the South and West when Biddle became president. These short-term (60-90 days), liquid, interest-bearing orders represented the value of agricultural exports and commercial imports. Their dissemination was intended to facilitate commerce along the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. Bills of exchange dated back to early modern Italy and bear some resemblance to a personal check one might use to pay rent today. They passed from hand to hand, but unlike bank notes, they required endorsements (signatures) for each transaction. Factors, planters, merchants, and other actors who engaged in long-distance trade used bills of exchange to avoid the time, risk, and hassle of transporting specie over long distances to pay for goods. The point was to connect buyer and seller in an efficient manner. By purchasing bills in exchange for issuing its own notes, the Second Bank of the United States was providing planters and other actors with cash that they could use to buy crops, slaves, tools, land, and other commodities. It greased the wheels of commerce. The bank’s credit was crucial in this instance because without it, the planter may have had to wait several months before his cotton reached its ultimate destination in Great Britain.

The loans that the Second Bank of the United States offered, expanded and contracted according to season. During the winter and spring months, when cotton was moving to market for export, the Second Bank's branches in the South purchased millions of dollars worth of foreign bills of exchange. These bills were denominated in British pounds sterling and drawn on (or payable in) London. The Second Bank of the United States would then ship these bills up to its northeastern branches, which sold them to American import merchants. By the summer and fall, the merchants would use these bills to pay for manufactured goods, which were then arriving from Great Britain. Meanwhile, the bank’s southern branches had issued notes to planters as part of the discount process. Planters could then pay their debts to southern merchants, who reimbursed northeastern creditors, who in turn, sent remittances to merchant banking houses. Over the course of the year, bills of exchange and bank notes flowed in a northeasterly direction.

The BUS repeated this process over and over on a nationwide scale involving millions of dollars, and in doing so it provided financial services that linked the needs of southern planters and northeastern merchants at very low cost to both. By purchasing bills in some locations and then selling them in others for only a small profit, the bank equalized and rationalized interregional exchange rates. It smoothed out seasonal fluctuations in trade and provided cheap credit where it was needed. Without these services, the availability of bills of exchange during certain months of the year would have run dry, leading to higher exchange rates. Merchants would have needed to ship specie to pay for goods, which was not cheap. By reducing the cost of interregional and international trade, the Second Bank of the United States contributed to the nation’s economic growth.

One might even conceptualize the Second Bank of the United States as a conduit for channeling northern and British capital into the mutually reinforcing booms of land, cotton, and slavery. Balance sheets indicate that BUS branches in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys were doing the most business and making the most profits compared to branches in other regions, especially New England. Of the 55 percent to 60 percent of BUS shares owned by domestic shareholders (the Treasury owned 20 percent while foreign stockholders typically owned around 20 percent), most were set aside for branch offices in northern states. Yet the Bank’s discounts, note circulation, and bills of exchange were concentrated disproportionately in slave states. From January 1, 1832 to January 1, 1833, all of the Bank’s branches purchased approximately $67.5 million in bills of exchange. Of this sum, $46.3 million, or 68.6%, were purchased at branch offices located in slave states. In February 1832, more than two out of every three notes issued by the Second Bank of the United States (67.9 percent) were issued by branches located in slave states.

Further Reading

Bodenhorn, Howard. State Banking in Early America: A New Economic History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Browning, Andrew. The Panic of 1819: The First Great Depression. University of Missouri Press, 2019.

Campbell, Stephen. The Bank War and the Partisan Press: Newspapers, Financial Institutions, and the Post Office in Jacksonian America. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2019.

Govan, Thomas Payne. Nicholas Biddle, Nationalist and Public Banker, 1786–1844. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959.

Knodell, Jane. The Second Bank of the United States: “Central” Banker in an Era of Nation-Building, 1816—1836. London: Routledge, 2017.

Smith, Walter Buckingham. Economic Aspects of the Second Bank of the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953.

Timberlake, Richard. The Origins of Central Banking in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978.